The Filing Fee Diaries - Ordinary People, Extraordinary Ideas

- Palak Dawar

- Sep 12, 2025

- 10 min read

Innovation is often portrayed as the playground of tech giants, research labs, or venture-backed startups. We picture Steve Jobs unveiling the iPhone, Elon Musk sending rockets into orbit, or Dyson turning vacuums into status symbols. But beyond this glossy narrative lies a quieter, grittier truth: some of the world’s most useful inventions come from ordinary people: janitors, porters, farmers, and nurses armed not with million-dollar R&D budgets, but with determination, a sketch pad, and a filing fee.

These unsung inventors rarely make headlines, yet their ideas shape our daily lives in profound ways. Every time you use an ice cream scoop, strap down cargo, or enjoy drip-free urinals in public restrooms, you are benefiting from the creativity of people you’ve probably never heard of. These individuals remind us that intellectual property (IP) is not just for the powerful but for anyone with an idea worth protecting.

This is their story, a testament to human ingenuity where everyday frustration sparks innovation, and where the simple act of filing a patent can turn a problem into a solution used worldwide.

The Janitor Who Patented Cleanliness - James M. Spangler

At the turn of the 20th century, department‑store janitor James Murray Spangler was losing a nightly fight with dust. Working as a janitor in Canton, Ohio, and struggling with asthma, he noticed that the carpet sweeper he used didn’t trap dust, and rather blasted fine particles back into the air, triggering coughing fits. Instead of accepting that situation, he started tinkering.

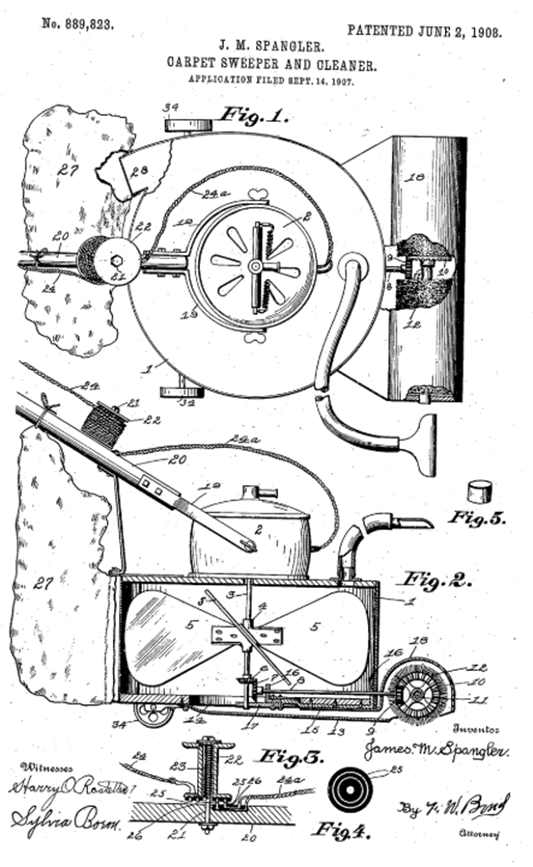

In 1907, he cobbled together a prototype from whatever he could scavenge: an electric fan motor mounted to a carpet sweeper body, a metal (soap) box frame, a rotating brush to lift debris, a broom‑style handle for control, and a satin cloth pillowcase to trap dust exiting the airflow path. Crude but effective. His breathing improved when he used it, so he refined the design and filed for protection. The U.S. Patent Office granted U.S. Patent No. 889,823 for his “Carpet Sweeper and Cleaner” on June 2, 1908, an invention widely credited as the first commercially practical portable electric suction sweeper for household use and an early design to incorporate a reusable cloth dust bag that would influence the modern upright vacuum.

Fig. 1 Image from patent: US889823

His cousin Susan Hoover was an early adopter of his machine, so when Spangler lacked the capital to mass‑produce and fell into debt, Susan’s husband William Henry Hoover acquired Spangler’s patent rights in 1908, retained Spangler as a partner, and launched what later became the Hoover Company. The 10-day free trial programs offered by the company helped spark adoption, and the product evolved rapidly under Hoover’s manufacturing muscle. Today, in parts of the world, “to hoover” still means “to vacuum”, a linguistic legacy rooted in a janitor’s asthma problem and a smart patent filing.

The Porter Who Perfected Ice Cream Service – Alfred Cralle

Rewind to the late 1800s. In 1897, Alfred Cralle, a hotel porter in Pittsburgh, noticed a problem that was both trivial and surprisingly hard to solve: serving ice cream efficiently. Back then, scooping ice cream was a messy, inconsistent process. It required two-handed techniques, frequent rinsing of utensils, and was far from efficient for busy parlors and hotels.

Cralle’s solution was elegant in its simplicity - a mechanical device for solving the problem. He invented a one-handed ice cream scoop with a built-in sweeper blade, designed to make serving quick and mess-free. He filed U.S. Patent No. 576,395, creating a tool so timeless that its basic design remains in use over 100 years later.

Fig. 2 Image from patent: US576395

Although there is not much evidence about him profiting off the invention, Cralle’s story is more than a historical footnote; it’s a lesson in endurance. He lived in a time when racial and economic barriers often prevented African Americans from receiving recognition for their contributions. Despite this, his invention endured, outliving both the patent’s legal protections and the era’s prejudices. Today, every ice cream shop, from small-town diners to global chains, owes a debt to a hotel porter who simply wanted to make life a little easier for the people around him.

The Firefighter Who Reinvented Hands-Free Lighting – Chris McCorkle

Chris McCorkle, a firefighter from Phoenix, knew firsthand how critical visibility was during rescue operations. Traditional handheld flashlights were cumbersome in smoke-filled rooms, forcing firefighters to juggle tools while maintaining a steady light beam. Determined to find a better solution, McCorkle developed a simple yet effective invention: the Blackjack Helmet Flashlight Holder.

This compact mount attaches a flashlight securely to a firefighter’s helmet, aligning the beam with their line of sight while leaving both hands free. His practical innovation quickly gained traction among fire departments across the country, as it drastically improved efficiency and safety during emergencies.

To protect his idea, McCorkle filed for a patent, resulting in U.S. Patent No. 9,039,228 B1 in 2015 for the “Flashlight Holder for a Helmet.” This legal protection not only safeguarded his design from imitators but also enabled him to build a business around a product born from real-world firefighting challenges.

Fig. 3 Image from patent: US9039228

McCorkle’s invention was featured on CNBC’s The Big Idea with Donny Deutsch, bringing national attention to the ingenuity that often emerges from everyday problem-solvers rather than corporate R&D labs. Today, versions of his holder are standard equipment for countless first responders.

Innovation Behind Bars – Roscoe Jones Jr.

For 11 years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, one of the U.S.’s most notorious maximum-security prisons, Roscoe Jones Jr. spent his days in solitary confinement. With minimal human contact and no distractions, he began crafting a board game called Serving Time on the River: The Harsh Realities of Prison Life. Hand-drawn and hand-colored, the game dials up the brutality of daily life: players endure assaults, medical emergencies, gang violence, and arbitrary “killed in prison” or “suicide” outcomes. It was Jones’s way of giving outsiders a visceral taste of confinement’s randomness and despair.

Later, his habit of smoking became an inspiration for yet another invention rather than solely being a coping mechanism to pass the time in jail. Boredom and concern over accidental fires led Jones to construct a self-extinguishing cigarette holder. Ingeniously using a recycled metal disk, threading, and a nail, he built a prototype that choked off airflow as the cigarette burned toward its end. The concept: if the holder tipped or lay flat, the cigarette would go out, mitigating fire risk. Despite his incarceration, Jones pursued legal protection. On February 12, 1991, he was granted U.S. Patent 4,991,595, titled Self-Extinguishing Cigarette with Fail‑Safe Tilt‑Ring. The patent describes a tubular holder with distributed perforations, limiting oxygen supply; a tilt-ring mechanism ensures the cigarette extinguishes if the holder tilts or lies flat.

Fig. 4 Image from patent: US4991595

Jones spent years writing from prison, attempting to pitch his invention to tobacco companies. None accepted. He never profited financially, his idea remained largely unadopted. But the patent stands as evidence of ingenuity thriving even under extreme conditions.

Stitching Safety into History – Garett A. Morgan

Garrett Morgan’s story is one of relentless ingenuity born out of necessity and compassion. Before becoming a household name in safety innovation, Morgan made his living in Cleveland, Ohio, as a sewing machine repairman and tailor. His keen mechanical skills and entrepreneurial spirit led him to experiment with different products, one of which was a hair-straightening solution he accidentally discovered while testing lubricants for sewing machines. This product became so popular that it funded his future experiments. But it wasn’t fashion or haircare that secured his legacy, it was his life-saving invention for firefighters.

The early 1900s were marked by deadly industrial fires, with the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire searing a tragic image into public memory. Morgan was deeply affected by the horrific loss of life, many of whom were garment workers just like those he worked alongside. He realized that most fire-related deaths were caused by suffocation from toxic smoke rather than burns. This insight drove him to design a protective breathing apparatus, one that could be worn in the thickest of smoke. By 1912, Morgan had developed what he called the “Safety Hood,” a forerunner to the modern gas mask. Unlike previous designs, Morgan’s device was simple yet ingenious: it consisted of a hood covering the head and a long tube that extended close to the floor, where the air was less toxic. Inside, a wet sponge acted as a filter for dust, smoke, and chemicals. In 1914, Morgan secured U.S. Patent No. 1,113,675 for his invention.

Fig. 5 Image from patent: US1113675

The world truly recognized the hood’s value in 1916, when an explosion trapped workers inside a tunnel beneath Lake Erie. While authorities hesitated to act, Morgan, equipped with his device, led a daring rescue that saved several lives. The event garnered national headlines, though Morgan, facing racial prejudice was initially denied public credit. Fire departments across the United States, however, began adopting his hood, which went on to save countless lives in both industrial accidents and wartime conditions, including its use during World War I.

Morgan’s inventive streak didn’t stop there. Building on his mechanical intuition, he later patented an improved traffic signal (U.S. Patent No. 1,475,024), one of the first to feature a “caution” signal between stop and go. This simple yet impactful innovation significantly reduced road accidents, cementing his place as a pioneer of public safety. Despite these accomplishments, Morgan’s legacy is most strongly tied to his safety hood. It was an invention born not from corporate R&D but from the heart of a man who saw preventable suffering and refused to look away. Even while creating products like hair-straightening creams or engineering better traffic lights, the thread running through Morgan’s work was a profound commitment to solving real, human problems.

Fig. 6 Image from patent: US1475024

The Engineer Who Cushioned The Ride – Robert William Thomson

Before paved motor roads, most travel meant iron‑shod wheels hammering over rutted surfaces - loud, jarring, and dangerous to passengers, wagons, and horses alike. Scottish inventor Robert William Thomson saw that the problem wasn’t just the road; it was the interface between wheel and ground. What if the wheel rode on air? His answer would become the first patented pneumatic tire, decades before cars, cycling booms, or John Boyd Dunlop. By isolating the carriage from impact and improving grip, Thomson was thinking about ride quality and safety long before transportation industries caught up.

At just 23, Thomson filed British Patent No. 10990 on December 10, 1845 for what he called his “Aerial Wheel”: a hollow India‑rubber tube enclosed in a leather casing and fastened to a wheel rim to create a resilient, air‑cushioned interface. He later secured a U.S. Patent (No. 5104, Aug. 5, 1847) covering the concept. Public demonstrations, including runs in London’s Regent’s Park in 1847, showed that his pneumatic tires dramatically reduced noise, softened vibration, and made carriage travel smoother and more controlled. The idea was radical: air as structure.

Fig. 7 Image from patent: US5104

So why didn’t the world switch immediately? Timing. In the 1840s there were no automobiles, bicycles were barely emerging, thin rubber was costly and scarce, and the market for premium, maintenance‑sensitive tires was tiny. Thomson’s tires did see use; reports note extended mileage tests (1,200 miles without serious wear) and that his own carriage still ran on them at his death but the invention was “too early.” Only decades later, when John Boyd Dunlop re‑introduced the pneumatic principle in the bicycle age, did air‑filled tires catch fire commercially, obscuring Thomson’s priority for generations. His contribution has since been restored: he’s now honored in the Tire Industry Hall of Fame and celebrated as the true pioneer of the pneumatic tire.

The Lady Who Couldn’t Stop Fixing Things - Beulah Louise Henry

Beulah Louise Henry didn’t train as an engineer, but she couldn’t look at an everyday object without thinking, ‘There’s a better way of doing that’ - a line later used by the USPTO to sum up her career. Born in Raleigh, North Carolina in 1887, she grew up sketching fixes for minor annoyances - flags that dragged, belts that wouldn’t hold papers, umbrellas that never matched outfits. Largely self-educated, she relied on sharp observation, fast sketching, and hired model makers to translate the devices she said appeared “fully formed” in her mind. By the time she was known nationally as “Lady Edison,” she had become one of the most prolific woman patentees of the early 20th century.

Her first U.S. patent, No. 1,037,762 (1912), covered a vacuum ice‑cream freezer that reduced labor at a time when mechanical refrigeration wasn’t widespread. She followed quickly with interchangeable‑cover umbrellas and handbags, ideas manufacturers initially dismissed until she built her own prototypes, opened the Henry Umbrella & Parasol Company in New York, and proved the market. That success funded a decade‑long inventive run in consumer products - toys, apparel aids, household tools, and office accessories designed to be simple to make and easier to use.

Fig. 10 Image from patent: US1037762

Highlights from her patent portfolio read like a tour of 20th‑century daily life upgrades: the Photograph duplicating attachment that produced multiple typed copies without carbon paper; a Bobbinless lockstitch sewing machine (U.S. 2,037,901 cited in her records) aimed at reducing thread snarls; snap‑on umbrella covers; Pneumatic Hair Curlers; Spring‑Limbed Dolls; the color‑changing “Miss Illusion” doll; Soap‑Filled Dolly Dips sponges; the Kiddie Clock for teaching time; and continuously attached mailing envelopes that streamlined business correspondence. In total she earned 49 U.S. patents and is credited with 100+ inventions, licensing many to manufacturers and sustaining herself as a full‑time professional inventor - an extraordinary feat when only a tiny fraction of patents were held by women.

Innovation Without Gatekeepers: The Universal Right to Create

What ties these inventors together isn’t money, social status, or formal credentials - it’s a refusal to shrug at broken systems. Each saw a problem everyone else had learned to live with, imagined something better, and took the step too many skipped, they filed. A patent application isn’t “just paperwork”; it’s a declaration that says, ‘This idea matters, and I claim it’. And while not every filing births a billion-dollar business, the cultural ripples endure. Alfred Cralle’s scoop changed how the world serves ice cream; Beulah Louise Henry’s fixes quietly upgraded everyday tools; and Garrett Morgan’s safety hood let rescuers breathe long enough to save lives. Patents expire. Impact doesn’t.

In a world obsessed with tech giants and billion-dollar valuations, it’s easy to forget that IP is a democratizing force. The U.S. Patent Office doesn’t care if you’re a Silicon Valley CEO or a janitor with a mop sketch; what matters is that the idea is new, useful, and yours. These stories aren’t just histories of clever devices; they’re proof of possibility. The next meaningful invention could come from someone cleaning, driving, farming, stitching uniforms, or serving time not just coding in a startup incubator. All it takes is curiosity, the will to build a fix, and the determination to protect and share that spark. That’s the real legacy these inventors leave behind.

Reading about how ordinary people turn simple ideas into something extraordinary really inspires me. It makes me think about the small innovations in everyday life that often go unnoticed but can have a huge impact. For instance, in industries relying on chemistry, even a tiny improvement in materials or processes can change outcomes significantly. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to explore more about chemical products it’s fascinating how the right compounds can drive innovation and efficiency. Articles like this encourage me to think creatively and see potential in ideas that might seem small at first glance.